My name is Inonge Kaloustian. My first name means “someone whom everyone loves” and my last name means “the good coming.” I was born and raised in the DMV, and have lived in gorgeous Prince George’s (PG) County, Maryland, since I was four years old. On June 13th, 2021, I graduated magna cum laude with high honors from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, a place that I found to be so incredibly different from home.

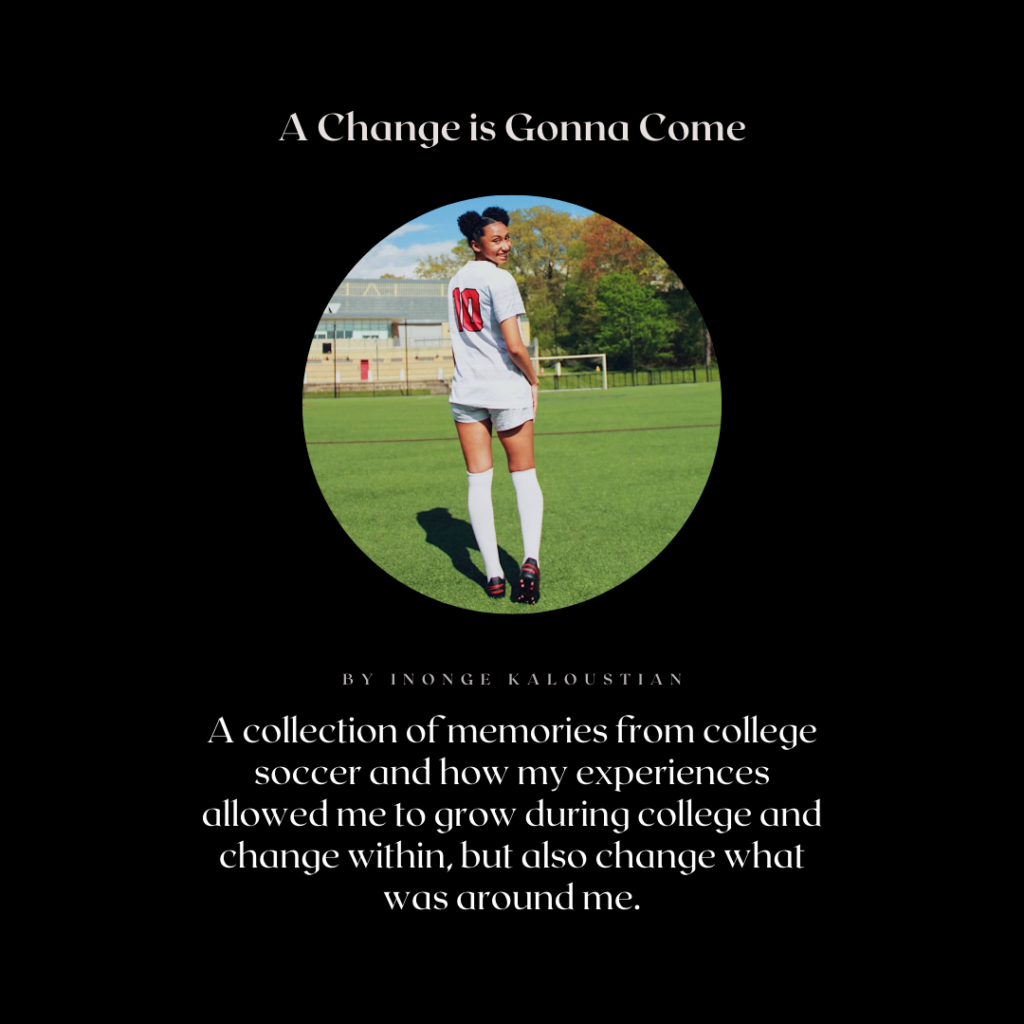

During my time at Clark, I participated in various extracurriculars and community service activities. One of the most defining groups I was a member of was the Clark Athletics department, of which I was a four-year member and one-year captain of the women’s soccer team, becoming the first Black captain in program history. I was also a women’s soccer representative in SAAC, the student-athlete advisory committee.

To be 100% truthful with you, when I was a senior in high school who committed to Clark to play soccer, I had no idea what to expect for the next four years. I had no clue what college soccer was all about, or about the schools in my conference, or about the impact being on the soccer team would have on me.

This was because unlike many other college soccer players, I didn’t join a club soccer team until the winter of my junior year of high school. The reason for this being, there were not many club teams in PG County—despite PG County being the most affluent majority-Black county in all of the nation, club soccer teams still are financially unattainable for many kids in the county, especially the ones attending public school. And, if you are able to afford a club team financially, a lot of parents can’t afford the time—my practices were a minimum 45 minutes away, with games usually further than that.

This is what is referred to as the “pay to play” model, which is why American soccer (on the men’s side at least) isn’t as highly regarded as the international scene. And many kids from PG County go on to play professional sports (see Kevin Durant, Kaila Charles, Jeff Green, Chase Young, Markelle Fultz, and lots more). Many kids from PG County even go on to play college soccer, but most of them were private school kids or played on an academy team, which would disqualify them from playing for their high school. Because of this, I knew very little about the college soccer recruitment process.

When I went to join my club team, my coach, Rob Kurtz, took me in with open arms. He took the time to explain how the recruitment process worked for college soccer, how to speak to coaches and carry myself on visits, and vouched for me when he spoke to coaches. For that, I’m forever grateful (shoutout Kurtz!).

For the majority of the time I was on my club team, I was the only Black player, and I was always the only player from PG County. I was way behind the other girls in terms of my recruiting process, and had to play catch up. It also didn’t help that I had no idea what I wanted from a college, and didn’t know how to narrow down my search. However, by God’s grace, and with a lot of help from my coaches and support system, I had a good amount of offers by the winter of senior year. They were mainly offers from small, liberal arts institutions like the rest of my club teammates had. In PG, my high school counseling consisted of one yes or no question, “are you applying to college?” The answer was yes, and then I was told I could leave the guidance counselor’s office. Because of this, I hadn’t heard about all these small, prestigious colleges that my club teammates were being encouraged to apply to. But, there I was, on August 19th 2017, standing in my new dorm 7 hours away from home.

When I first got there, I was soaking it all in. My roommate was one of my teammates, I was on the field six days a week, had every class with at least one teammate, and pulled up to every party 27 players deep. We did everything together and I loved it; I didn’t participate in anything outside of the soccer team. However, as time went on and I got more comfortable with my team and other student-athletes, things started happening.

A stray N-word in a song here, an ignorant comment about my hairstyle there, etc. And I would always call it out, no matter who it was. Because I had never lived in an environment where I was the racial minority, I truly thought these comments were just an unfortunate series of events happening in my first year at college. I didn’t realize that these were common occurrences amongst white youth. Whenever I did call out any type of racist or ignorant behavior, I found that it always came back to bite me in some way. People thought me calling them out meant I “hated them,” I was constantly being labeled as that mad, Black girl, and so on.

My sophomore year was no different, except I started to be more open about what I was experiencing, and found a support system outside of athletics, mainly within affinity-based clubs on campus like the Black Student Union and Caribbean-African Student Association.

This wasn’t a very common practice, as we had something on our campus called the “Clarkie/Cougar divide.” As you can imagine, Cougars were the student-athletes and Clarkies were the non-student-athletes. The groups rarely overlapped. At this time, I became friends with another Black woman within the athletics department who had just stepped away from her team because of the microaggressions she had been facing. Ahiela was also from a majority-minority community (Brockton, we live!), and like me, she found the athletics environment to be less than inviting for Black women. We also noticed that there was a constant stream of athletes of color stepping away from their teams or leaving Clark altogether. So, we approached our athletic director with a list of our concerns in the fall of 2019. These concerns included the lack of urgency in addressing matters of ignorance or bigotry amongst members within the athletics department, the poor retention rate of student-athletes of color, and the lack of non-white coaches and support staff. However, it appeared as if these issues affecting the department that were clear as day to us were not as salient in others’ minds.

From here, we formed a small working group of a few athletes and coaches who our athletic director felt were like-minded and were interested in working to make Clark Athletics more equitable. Things were…messy at first to say the least. We had no name, no mission, and no concrete goals in mind to address the things we were unhappy with about the athletics department. However, over time, our goals started to solidify and we learned how to work together. We got better at learning how to facilitate meetings so that everyone could benefit from the conversation. This was definitely the hardest part of the process for me personally—it was really intimidating for me to lead a conversation surrounding racial justice in a room full of white men. However, I’m sure that’s not the last time I’ll be put in that situation, and so I’m glad that I got experience navigating a space like that earlier on in my career.

In my last two years at Clark, we were able to accomplish quite a bit as one of the newer clubs on campus. We established regular meetings amongst athletes to discuss issues we saw in our department or within athletics in society as a whole. We also held a meeting and subsequent ‘field day’ between athletes and non-athletes to address the aforementioned divide on campus. I was able to represent Clark Athletics at the 2021 Black Student-Athlete Summit hosted by UT-Austin as a featured speaker, and we’ll be sending student-athletes to this year’s New England Regional Black-Student Athlete Summit hosted by UMass Amherst. Because three of us on the CAIC executive board worked as admissions ambassadors, we also are trying to change the culture and image of athletics from the point of view of the admissions office in order to cultivate a more amicable relationship between athletes and non-athletes. Because of the strides we’ve made in the department, we were granted the Inaugural President’s Achievement Award for Inclusive Excellence from university leadership.

And it really wasn’t all bad. I firmly believe that I was meant to be at Clark for a reason, and I have no regrets. The connections that I’ve created along the way are life-long, and the lessons I’ve learned in the classroom and on the field are irreplaceable. By the time I graduated, I had gained such a solid support system, and what more could I ask for? I can only hope that I’ve impacted Clark in the way that it has impacted me.

Although I have one more year of eligibility to play college soccer, and will be attending graduate school, I’ve decided to step away from being a player and fill some other shoes instead. I’ll be returning to my high school as a volunteer coach this fall, and could not be more excited. The past year or so, I’ve been helping out by leading a few online Q&A and workshop sessions for girls from my high school who are curious about playing soccer in college or just college in general, and look forward to getting to know them more. If you don’t know me personally, my career goals include becoming a physician-scientist, and I always said that my first paycheck would be split between my family and a donation to my high school. And while I can’t exactly donate money right now, I can donate my time to the team. And so, I leave you with one of my favorite quotes by James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” It’s my hope that the change I’ve helped make at Clark and now at my high school have a long-lasting impact, and that everywhere I go in life, I have the strength to continue to face the things I want to change.

About the author

Inonge Kaloustian is a recent graduate of Clark University in Worcester, MA, where she was a four-year member of the women’s soccer team. In her time at Clark, she became the first Black captain of the soccer program and co-founded the Clark Athletics Inclusion Coalition, which is an organization focused on sparking conversation regarding social equity within athletics. This fall, she will be continuing her education at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, studying for a Master’s degree in Epidemiology.